Published in the Conversation, National Post and Calgary Herald, March 27, 2019

With Martin Olszynski (University of Calgary) and Deborah Curran (UVic)

In the fall of 2018, we suggested that post-truth politics were sinking the debate with respect to Bill C-69, the current government’s attempt to restore some credibility to Canada’s environmental assessment regime.

While we called for calmer and better-informed debate, the situation appears only to have worsened.

In February, a truck convoy rolled into Ottawa from Alberta, decrying carbon taxes, immigration and, yes, Bill C-69.

The rhetoric has become so heated that the Senate Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources, currently studying the bill, felt compelled to take the extraordinary step — for a Senate committee — of conducting hearings in nine communities across Canada on the legislation.

Notwithstanding its opponents’ criticisms, Bill C-69 largely leaves the existing assessment and review process intact, established in its current form by the Harper government’s 2012 omnibus budget bills (Bills C-38 and C-45).

Relative to that regime, Bill C-69 would restore the pre-Bill C-38 rights of members of the public to participate in assessment processes. It would also require that cabinet provide clearer explanations of the reasons for its decisions under the act, strengthen provisions for Indigenous peoples’ participation in the assessment process and modestly restructure the National Energy Board, including by renaming it the Canadian Energy Regulator.

Far fewer assessments

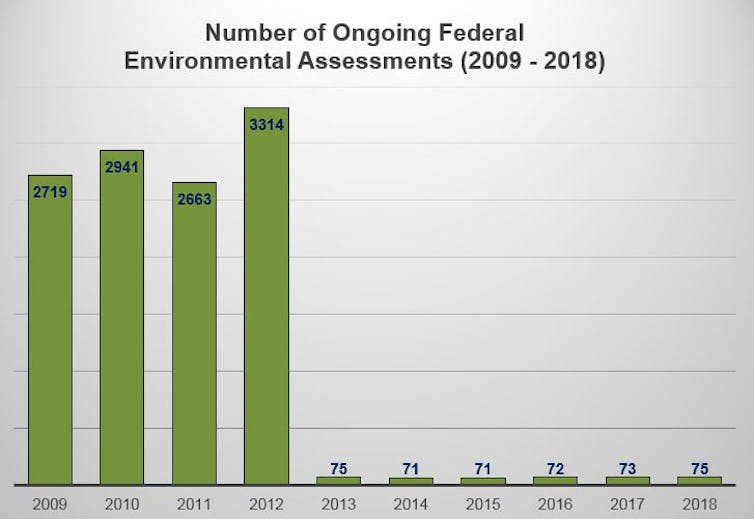

The resulting system would remain a shadow of what existed before 2012. Before then, several thousand federal environmental assessments were conducted each year. Under Bill C-69, the new impact assessment process would likely remain limited to roughly 70 projects per year:

To put this in concrete terms, there are currently only two projects undergoing federal assessment in Saskatchewan, four in Manitoba and seven in Alberta. The Alberta Energy Regulator, in contrast, processes roughly 3,500 applications for new projects per month.

Importantly, Canada’s resource industries have been successful with some form of federal environment assessment regime for more than 40 years, most of the time under systems that were far more robust than what Bill C-69 would leave in place.

As we noted previously, the bill’s development was the subject of two years of extensive engagement with industry, parliamentarians and the public. That engagement included the work of two expert panels that travelled across Canada and published comprehensive reports, and a House of Commons committee that heard testimony from more than 100 witnesses.

Part of the problem seems to be that the bill has become a proxy for wider concerns about the impact of the cyclical nature of the oil industry, and the consequences of excessive economic dependence on exports of a single commodity.

These issues have been brought to a head again over the past few years by weak global oil prices. Although these problems have been well-recognized in some quarters of western Canada for years, a succession of governments, provincial and federal, have failed to address them effectively.

Doubling down

Instead, they have tended to double down on the same dependencies, the most recent example being the federal government’s purchase of the Kinder Morgan/Trans Mountain pipeline.

It’s also important to remember that the opposition to Bill C-69, although very vocal, is actually surprisingly narrow. Recent public opinion polls suggest the bill is virtually a non-issue with Canadians beyond the oilpatch. The legislation has also garnered moderate support from other resource industries, Indigenous communities and environmental organizations.

At the same time, many Indigenous representatives and environmental advocates feel the bill falls far short of what is needed, both in terms of advancing environmental sustainability and meeting the requirements of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The bill’s opponents seem to have also lost sight of why environmental assessment processes were invented in the first place.

Their development reflected, first, a recognition of the need for better decision-making processes around projects to ensure that the full range of their economic, environmental and social impacts and risks were understood before they were allowed to proceed.

The second key consideration, in Canada’s case, was more political. Environmental assessment processes grew out of a need for governments to resolve conflicts over the risks, costs and benefits associated with major projects in a way that’s seen as legitimate by those affected. They’re also aimed at limiting the collateral political damage that such conflicts can inflict.

Most projects allowed to proceed

The possibility of a decision not to proceed if the costs, impacts and risks of a project are found to be unacceptable remains essential to establishing the legitimacy of the process.

In practice, in the vast majority of cases, projects are allowed to proceed with environmental risks mitigated by imposing conditions.

Critics of Bill C-69 appear to have lost track of all this.

Rather, they seem to be demanding an amplification of the 2012 model that enables governments to rubber-stamp complex and controversial projects while avoiding the messy business of actually identifying and addressing potential trade-offs among environmental, economic and social goals that projects may necessitate.

That approach will continue to lead to outcomes that are seen as illegitimate by many of those affected — exacerbating, rather than resolving, the social, legal and political conflicts around any given project.

That’s already evident in the successful court challenges of the approval of the Northern Gateway and Kinder Morgan/Trans Mountain pipeline projects whose approval was a major goal of the Bill C-38 amendments. These issues are particularly important in terms of fulfilment of the Crown’s duty to consult with Indigenous communities.

Canadians would be better served by a calmer and better-informed debate over the specifics of Bill C-69 than what we have been seeing over the past few weeks.

Whether we’ll get to such a discussion now largely rests in the hands of a Senate committee, which will have to choose between further fanning the flames of conflict over the bill or providing some meaningful sober second thought on its actual contents.